Despite pressure to produce more food in an increasingly challenging climate, the U.S. is adopting precision agriculture technology, according to the General Accounting Office's latest assessment of the benefits and challenges of agricultural technology. of farmers and ranchers, only 27% of them.

According to the report, the percentage of technologies used across the country is:

-

Automated guidance systems were used on 58% of corn acres and 54% of soybean acres.

-

Yield mapping was used to plant 44% of both corn and soybean crops.

-

Variable rate techniques were used on 27% of corn and 25% of soybean acres.

Farmers who use precision technology can increase profits and reduce the use of fertilizers and herbicides, the report said. It also reduces fuel consumption, conserves water, and prevents excess chemical and nutrient runoff.

However, a lack of standards, data sharing concerns, and high initial costs are hurdles to adoption.

“Equipment is very expensive to get into precision agriculture,” says Brian Boswell, director of GAO's Science and Technology Assessment and Analysis Team and author of the technical report.

“if [the farmer] Because you don’t buy from the same manufacturer, you may have equipment that doesn’t communicate with each other,” he says. “They're different. There's no interoperability. It's not easy or cheap to replace one of them.”

The January report broadly defines precision technology to include emerging machines such as drones and ground robots. Other technologies include more established technologies such as underground sensors, targeted sprayers, automated mechanical weeders, and even automated guidance systems.

various crops

The seemingly low national adoption rate of precision technologies may be related to the diversity of U.S. crops.

“If you look at the technology costs for cotton, they tend to be higher than the costs for soybeans,” said Jonathan McFadden, a research economist at the USDA Economic Research Service. “Adoption rates vary widely.”

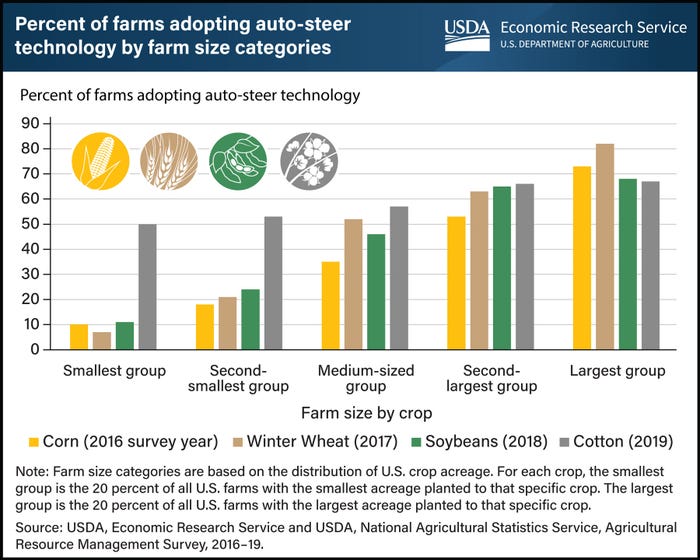

Yield mapping went from being used on 5% of soybean acres in 1996 to just under 45% in 2018, according to the USDA's latest report on precision agriculture adoption, which McFadden helped author. Adoption rates were similar for maize. Similarly, in the late 1990s less than 5% of corn acres were planted using autostairs, but this has steadily increased. Currently, half of the acres planted to these crops are managed through self-direction.

Crops such as winter wheat, rice, cotton, and sorghum have been slow to adopt new technologies due to the high cost of plant-specific precision technologies.

U.S. farms have adopted precision technology at varying rates, with the largest farms adopting autopilot guidance technology at significantly higher rates.

There is also a stacking effect. Some farmers use more technology than others because implementing advanced systems such as variable rate applications requires basic technology such as soil mapping.

“It's well known that farmers who use variable rate techniques tend to do so because they do soil analysis. They have soil maps,” says McFadden. “Farmers use [data-tracking] technology after that. You could even think of that as a prerequisite. ”

This appears to be the case at RD Offutt Farm in Fargo, North Dakota. Since its founding in the early 1960s, this family farm has employed techniques to maximize yields on sandy soils.

“We are committed to soil health, conserving water, and keeping our food supply safe and secure,” says Jennifer Maretzke, the farm's director of communications and external relations.

Over the years, Maritzke says this thinking has helped produce higher yields while increasing efficiency and environmental sustainability. They use precision technology throughout the operation, including soil mapping, variable rate fertilizer application, application boundaries using John Deere's iTEC Pro software, soil moisture monitoring, and ultrasonic flow meters to conserve water. Masu.

“We continued to use proven methods such as digging shallow and deep holes in the soil so that we could directly check potato growth and soil moisture. We also use more advanced technology to better understand water usage and ensure accurate water usage reporting,” Mareitzke says.

Crop dispersion may explain why farms in certain states use more technology than others. More than half of farms in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa and Illinois are using precision farming techniques such as variable fertilizer application and yield monitoring, according to the GOA report.

In California and Kansas, 40% to 49% of farms use precision technology, and 30% of farms in Michigan, Minneapolis, Indiana, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Wyoming ~39% use precision technology. Only 10% to 19% of Wisconsin farms use precision technology.

Correlation of farm size

The study found that adoption of precision increases with farm size. “If you're farming 10,000 acres and you buy this $2,000 widget and use it across your farm, the cost per acre is relatively low,” says Bruce Erickson, clinical professor of digital agriculture at Purdue University. . “That's a lot of money” for a farmer working on 500 acres.

Erickson believes that small farms are losing opportunities to adopt this valuable technology due to economies of scale. “What is precision farming?” [technology]There are more economies of scale,” he says. “What my colleagues are concerned about are smallholder farmers in Asia and Africa. They have been largely left out of this digital revolution.”

ease of use

Adoption also depends on complexity. For example, automated guidance systems are easily understood and widely used. Boswell says this is because there is no steep learning curve.

According to Ericsson's annual survey of equipment dealers, most farmers use guidance, have yield monitors, and use on/off planter controllers and sprayer protection controllers. In comparison, “less than half of farmers use variable rates of pesticides when comparing nutrition and seeding rates,” he added.

The GOA report agrees with Erickson's assessment. Technologies that are relatively easy to use will be adopted more quickly. Conversely, the report says, “data-intensive technologies that require farmers to collect, collate, analyze, and act on data have high barriers to entry and have not been widely adopted.”

Demographics are another variable to keep an eye on. The report notes that younger farmers tend to adopt precision farming techniques faster than older farmers. (According to the 2022 Census, the average age of a farmer in the United States is 58.1 years old.)