BLOOMINGTON — Darrell Lawrence began this discussion with an introduction to the green-box Fish Low Kay Tor, one of the first applications of sonar technology to the recreational fishing industry in the early 1960s. .

This discussion and technology have come a long way since then, as evidenced by the participation of outdoor enthusiasts from around the state in Bloomington on January 19th for an annual roundtable hosted by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. I have accomplished it.

“So it's clear that there have been huge technological advances in fishing over the last few years, and that's what's getting everyone's attention right now,” said Jeremy Smith of Linder Media. He was speaking as part of a panel in one of the most lively conversations at the event. It focused on technology for fishing and hunting.

Mr. Smith was talking about forward-facing sonar and its cousins, including traditional sonar, down-imaging sonar, 360-degree, bilateral, and live sonar systems. Forward-facing sonar allows an angler willing to pay as much as $2,500 for his unit to literally see the fish and their reactions to lures in real time.

“It's absolutely amazing,” Smith said of the new electronics technology. “You know what's out there. Sure, fish can hide, but often the mystery disappears,” he added.

Anglers now have fishing grounds they never thought existed. Smith said they can target smallmouth bass and panfish in their deep-water nests during late-season spawning runs that no one knew about or even knew happened where.

Muskie anglers are most concerned about the effects of new technology, even though they are using it. Smith said muskie numbers are declining in pressured lakes because the big fish are easier to spot with sonar. He also noted that the DNR does not currently have a management plan for the fish.

Another source of controversy is the use of this technology to locate floating crappie and walleye in deep water. A YouTube video of a crappie being hoisted up from the ocean floor and experiencing barotrauma has sparked a lot of discussion. Mortality of panfish pulled from deep water for catch-and-release sportfishing is a very hot topic in the fishing world.

Mark Bacigalupi, panel member and DNR Fisheries Supervisor for the Northwest Region, said the DNR currently has no plans to regulate the technology. He explained that the DNR believes it has the tools to monitor fish stocks and can adjust harvest limits as needed.

He is an early adopter of forward sonar. “I think it’s going to be a lot of fun,” he said.

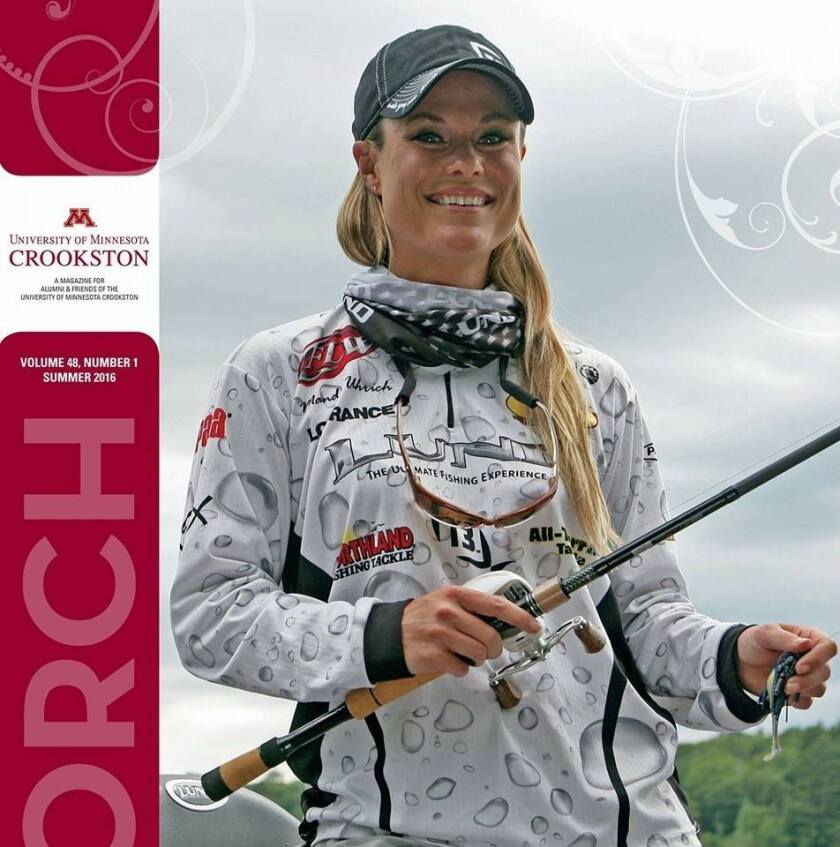

DNR panelist and biologist Mandy Urich agreed. She is a fishing guide, professional tournament competitor, and perhaps the most famous female angler in the state. She takes advantage of all the best technology, and we expect her use of it to continue to grow. “You have to be as prepared as possible to stay ahead of the game,” she said.

The good news, she noted, is that the technology has empowered nontraditional users and opened the door to the sport of fishing for more women.

Urich believes improving fishing and hunting skills is important for new entrants to the sport. Unfortunately, she said, the days of the traditional white male hunter and fisherman are over. “It's about making those resources available to the entire population,” she said.

contributed

Jimmy Bell, president of the Student Anglers Association, was not a member of the panel but made similar points during the discussion. He believes modern technology is especially important for recruiting young anglers. Quoting Al Rinder, he said: “You have to catch fish to keep them hooked.”

The contradiction pointed out in the discussion is the discrepancy between the accepted techniques for fishing and hunting. There are no restrictions on fishing, but there are restrictions on hunting.

The use of drones for hunting purposes is prohibited and the use of electronic devices is also restricted. Although the use of GPS is permitted, it is illegal to use electronic devices to film the game. For example, it is illegal to rush to search for large sums of money after a remote camera sends an image of it to your cell phone. However, a DNR enforcement officer who participated in the discussion said that while the law is in place, it is very difficult for officers to make their case. “We will do everything we can,” he said.

Our North American model for fish and game harvesting is based on the principle that wildlife belongs to everyone and everyone should have the right to hunt and fish. While more people enjoy non-consumptive activities such as catch-and-release and nature viewing, people who hunt and fish remain fundamental to conservation.

“We have to hunt and fish,” said panel member Phil Seng. He is a natural resources communications specialist at DJ Case and Associates in Indiana and a board member of Orien the Hunters Institute. The organization supports the free pursuit ethics underlying the North American model.

“How big is the hunt?” Sen said, emphasizing what was important. Whether it's fishing or hunting, we have the skills to ensure you get everything you want.

“Is that what we want?” he asked. He explained that America's hunters and anglers proposed the limits we have in place to protect resources, democratize harvesting, and create opportunity for everyone.

Photo by John Marshall

The challenge, he says, is figuring out where to draw the line. He emphasized that it is important for the DNR to communicate with constituents and know what they want and expect. Finding the right place to draw the line was always a problem. “We have to accept that and do our best to please as many people as possible over the long term. That's what it comes down to.”

At this point, installing all the best electronics available can require a six-figure investment, Smith noted. But make no mistake, costs are coming down and more people are investing in technologies like forward-facing sonar. Bacigalupi said the DNR is starting to ask anglers about their use of forward-facing sonar when conducting creel surveys. So far, usage rates have shown to range from 2% to 13%, with variation primarily by region. He added that many believe the actual usage rate is higher than what the Creel survey showed.

West Central Tribune/File photo