Kathrin LaFaver, MD, a neurologist and lifestyle medicine specialist from Saratoga Springs, New York, interviewed Dean Ornish, MD, the founder and president of the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute in Sausalito, California, and a clinical professor of medicine at the University of California in San Francisco and San Diego, about his recent study on intensive lifestyle modification to slow progression of mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). What follows is an edited transcript of their discussion.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: I have the great pleasure today of talking to Dr Dean Ornish, a pioneer in the field of lifestyle medicine. He has many accolades to his name and is well known for bringing lifestyle medicine approaches to cardiovascular disease. But the reason we’re talking today is the recently published study in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy on intensive lifestyle interventions for mild cognitive impairment and early AD. So, welcome, Dr Ornish.

Dean Ornish, MD: Thank you, Dr LaFaver. Great to be here.

LaFaver: Could you start off by giving us the background to the study that was just published?

Ornish: Sure. I think we’re at a place with early-stage AD very similar to where we were with coronary heart disease 46 years ago, when I began doing studies in that area. At that time, it was thought that once you had heart disease, the best you could hope for was to slow down the rate at which it got worse.

We know that what’s good for your heart is good for your brain because they share so many underlying biological mechanisms — things like inflammation, oxidative stress, changes in the microbiome, telomeres and gene expression, angiogenesis, changes in immune function, overstimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, and so on. My wife and I wrote a book called Undo It! a few years ago that put forth this unifying theory. Why is it that the same lifestyle changes — in essence, to eat well, move more, stress less, and love more — can affect so many common chronic diseases?

And it’s because they share so many of the same biological mechanisms. AD runs in my family. I have one of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 genes; my mother and all of her grandparents died from it. I have a personal interest in the rate of progression.

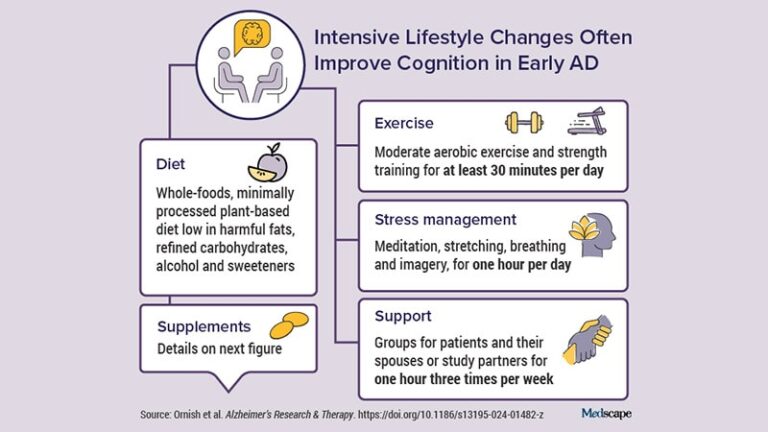

And so we designed a randomized controlled clinical trial with men and women who had either mild cognitive impairment or early-stage AD (most had early-stage dementia due to AD). We used the same lifestyle interventions — a whole-foods, plant-based diet that’s low in fat and sugar; moderate exercise; meditation and other yoga-based stress-management techniques; and support groups — that in previous studies not only reversed the progression of early-stage heart disease, for many patients, but also type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and early-stage prostate cancer. And so this was really the next logical step in that progression.

LaFaver: What were the main findings?

Ornish: After 20 weeks, what we found for the first time in a randomized controlled trial is that an intensive lifestyle intervention, without drugs, significantly improved cognition and function in many patients who had mild cognitive impairment or early-stage AD.

That’s important because, as you know, only three drugs (aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab) have been approved in the past 20 years, even though billions of dollars have been spent on drug development. All three are designed to pull amyloid out of your brain, and because of that, they can lead to cerebral hemorrhage or edema. Lecanemab was approved by the FDA about a year ago, and more recently, donanemab. They just slow the rate of progression, but if you’ve got AD, getting worse more slowly is still getting worse. It takes people’s hope away. As you know, the suicide rate 3 months after getting a diagnosis of AD is seven times higher because when you take people’s hope away, when you lose your memories, you lose everything.

Not every patient in our study got better, but our primary outcome was the same measures of cognition and function that are used in FDA drug trials. That is the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC), the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog), the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), and Clinical Dementia Rating Global (CDR-G). And in three of the four measures there was overall success and significant differences between the intervention group compared with the control group. For the fourth measure, the intervention group got worse a little more slowly, whereas in the control group, all four measures got worse.

LaFaver: Was there a link between the intensity of the lifestyle changes and changes in cognition?

Ornish: We also found a dose-response correlation using this a priori formula (the Lifestyle Index) that took into account all four aspects of the lifestyle intervention. This dose-response correlation was seen in all four measures of cognition.

Drs Steven Arnold and Rudy Tanzi also measured biomarkers at their labs at Harvard and Mass General. One was the Aβ42/40 ratio which, as you know, is a measure of amyloid. Because the antiamyloid drugs pull amyloid from your brain, your blood levels go up and that’s what we found with our lifestyle intervention; it did the same thing. In the drug trials, the Aβ42/40 ratio went down in the control group, presumably because there’s more amyloid going into the brain. We found the same thing to the P =.003 level. What really amazed me was that we found a dose-response correlation between the degree of lifestyle change and the degree of change in Aβ42/40 ratio.

I think that lifestyle changes in many ways worked better than these drugs, at a fraction of the cost. These drugs are very expensive. Lecanemab is about $26,500 per person and there are other associated costs: infusion costs, PET and CT scans, and so on. The drugs also have side effects and they don’t work as well in women, even though twice as many women as men get AD. And they’re not recommended for people who are homozygous for APOE ε4. The lifestyle changes not only slow the rate of progression but they often cause improvement. And that’s important because we can give people a sense of hope. For 71% of people in the intervention group, the CGIC score showed that progression of their disease stopped or reversed, whereas in the control group 68% got worse.

LaFaver: Why do you think lifestyle changes may be more effective than antiamyloid drugs?

Ornish: I think amyloid is an important part of the pathophysiology of AD, but it’s not the whole story. It’s one of the mechanisms, and if you’re just focusing on that one mechanism, you have some benefit; it slows the rate of getting worse. Lifestyle changes work on the Aβ42/40 ratio, but they also work on all these other mechanisms that I mentioned earlier: chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and so on. I think that working on many mechanisms at the same time is what it takes to show improvement in cognition rather than just slowing the rate of progression.

It may be that the future of AD treatment is a combination of both; it’s not necessarily this or that, especially as we get more effective drugs. By analogy, we often recommend statins and lifestyle changes for people who have severe coronary disease.

I think these findings are really important because when you take people’s hope away, that often becomes self-fulfilling; it’s almost like the brain shuts down as an adaptive response to this devastating news. We’re not giving people false hope — not everybody gets better — but we’re not giving that false despair either. Many people get better, and they get better to the degree that they make these lifestyle changes.

What we’ve found from all of our studies over the past four decades is that it’s hard to reverse the progression of a life-threatening chronic disease because most people don’t go far enough. Miia Kivipelto, MD, PhD, the internationally known AD researcher from the Karolinska Institute who collaborated with us on our study, published a paper on the MIND-AD study, around the same time in the same journal. She found that moderate changes slow the rate of progression, but more intensive changes may be required to stop — or in many cases, improve — AD.

LaFaver: Thank you for highlighting all the outcome measures because it’s important to not only look at the behavioral measures but also what we are changing biologically. I’d like to dive in a little deeper on the details of the intervention.

This is an intensive lifestyle intervention, and although not necessarily expensive, it’s not easy to do. In terms of the diet, the participants were provided with prepared food for the vegan low-fat diet. What would a typical week look like for a participant in the intervention group? What about the long-term feasibility for people who want to try this but don’t have the luxury of a private chef or having their meals prepared?

Ornish: We provided their meals because we wanted to test the hypothesis. To have any chance of showing improvement, we knew they’d have to follow the program really well, so we wanted to make it easy for them to do that. If they followed the program really well and it didn’t do anything, that would be disappointing, but that would be an important finding as well. People would need to know that so they didn’t fool themselves. But if they didn’t follow it, or they followed 75% of it, we knew that probably wasn’t enough to show improvement, and then we really wouldn’t be able to say much of anything.

We went to a lot of effort and expense to provide three meals and two snacks a day for the 20 weeks of intervention for the patient and their spouse. We met with them three times a week, for 4 hours at a time: an hour of exercise, an hour of meditation, an hour-long support group, and an hour listening to a lecture. It was a big commitment.

There were selected supplements as well. I have no financial relationship with any of the companies that make the supplements. It was the same lifestyle intervention that we’ve been studying for 45 years and that Medicare created a new benefit category for in 2010 for reversing heart disease. When COVID hit, they began covering it virtually through Zoom. I thought it was too high touch to be done via Zoom, and if anything good came out of COVID, it was learning that it worked just as well.

It also made it possible for us to collaborate on this study with some of the leading neurologists in the world, such as Jonathan Artz at the Renown Health Institute of Neurosciences, in addition to those I already mentioned at the Karolinska Institute. People like that can recruit and test patients locally. We would send the food and do the intervention virtually via Zoom.

We have data on over 15,000 cardiac patients who’ve gone through this; 93% of the people who start the Medicare program, which is twice a week 4 hours at a time for 9 weeks, finish all 72 hours. Some readers might be thinking, That’s crazy! I can’t even get my patients to take their statins. About two thirds of people who are prescribed statins are not taking them a month later, and the reason is because statins don’t make you feel better, but the lifestyle changes do. These biological mechanisms are very dynamic in both directions: You can feel better quickly, you can feel worse quickly. When people with heart disease make these lifestyle changes, they generally feel so much better so quickly. Their angina usually resolves or is much better in just the first 3 weeks. The motivation changes from fear of dying to joy of living.

Fear is a very powerful motivator, but only for a month or so. If someone’s had a heart attack or they are recently diagnosed with AD, you can get them to do pretty much anything you say. But then they stop and the denial comes back. Fear is not sustainable because we all know we’re gonna die, but we don’t think about it most of the time.

Joy, pleasure, and love really are sustainable. When you make intensive lifestyle changes — you change several things at the same time — paradoxically, it’s often easier than small changes like taking a pill because these lifestyle changes work so quickly that, in many cases, you feel much better quickly.

The angina resolves for someone who can’t walk across the street without getting chest pain. They can make love to their spouse or play with their kids or go back to work within a few weeks, in most cases. I’ve heard them say things like, “I like eating cheeseburgers, but not that much,” because what they gain is so much more than what they had to give up. That’s what makes it sustainable. In the case of AD, we found that it takes maybe 18-20 weeks, sometimes as early as week 12 or 13. But usually around week 18 or 19, people often report improvement in their cognition.

For someone who says, “I used to love reading books, but I stopped because I couldn’t remember what I just read” or “I used to like watching movies but I couldn’t follow the plot,” they notice improvements. Now, such anecdotal evidence in and of itself is not proof.

Dean Ornish, MD, interviews a patient who participated in the study, Tammy (and her husband Paul). Tammy is homozygous for APOE4.

LaFaver: This was a relatively small study. You intended to enroll 100 patients but ended up with 51, about 26 in each group. Could you comment on this?

Ornish: That question always comes up: It may be statistically significant, but what does it really mean clinically? But for many people, these clinical changes are quite big. There’s a common misconception that if a study doesn’t have 1000 patients, it’s not really definitive. But the scientific method, whether you’re studying lifestyle changes, a drug, or a device, is about measuring whether the changes are real or due to chance. And by convention, as you know, if there’s less than a 5% probability that these findings are due to chance, it’s considered statistically significant.

How do you get that? Well, you need to show bigger changes that are more consistent, with less noise, using accurate, reproducible measures in a small group of patients. You need to have a larger group of people to measure a less effective intervention. By analogy, if you were looking at the effects of penicillin on pneumococcal pneumonia in 1950 before there was drug resistance, and you had 50 people and half of them got penicillin, you don’t need 1000 people to know that it’s working. That’s similar to what we’re finding in our study.

Now, it makes it less generalizable because we didn’t have the diversity; but showing statistically significant differences in a smaller sample just means the intervention is that much more potent.

LaFaver: In addition to the diet you mentioned, there were a number of supplements. I was curious about the decision-making around which supplements to include. The conventional wisdom in lifestyle medicine is that if you eat a whole-food, plant-based diet, most people do not need many supplements except for vitamin B12, which is mostly found in animal-based food sources. Would you say this should be tested further in larger samples before we’re ready to make specific recommendations — such as probiotics, for example — even though the study showed that participants had changes in their microbiome following the intervention?

Ornish: Let me parse out what you’ve asked. Rob Knight, one of the leading microbiome experts in the country, did the microbiome studies at UC San Diego. We found that two organisms that are associated with a higher risk for AD went down in the intervention group and went up in the control group, and that organisms that are associated with being protective against AD increased in the intervention group and went down in the control group. Those changes were highly significant.

For me, it’s all about the risk ratio: What’s the risk, the cost, the side effects? When I designed this intervention 45 years ago, I wanted it to be available for everyone. It’s not just for affluent people. A cheap pair of walking shoes; meditation doesn’t cost anything; it’s essentially a Third World diet — the way people ate before they could afford all the junk food — and spending more time with your friends and family.

The supplements are the only thing that really cost anything. Again, I have no financial relationship with any of the manufacturers, but there’s independent evidence that each of them may play an important role. I figured, let’s do everything we can that might be beneficial, because in the context of a drug like lecanemab that costs $26,500, the cost of these supplements is fairly minimal.

LaFaver: We certainly need more doable interventions, and the nice thing is that people can start today; we don’t need to wait. So, what’s next? Are you planning on a longer-term follow-up of the study participants or larger-scale studies?

Ornish: Yes, we’re following these patients for another 20 weeks. In a drug trial, you can just withhold the drug and give placebo to the control group. But with a behavioral intervention you have to ask people, “If you are randomly assigned to the intervention group, would you be willing to make all these lifestyle changes?” And if they say yes, then you randomize them. They’ve made a mental commitment, so if they end up in the control group, you can’t stop them from doing it. But if both groups make lifestyle changes, you can’t show anything, obviously. So, the deal we made with the patients is that if you end up in the control group, just keep doing what you’ve been doing; don’t do anything new. And then after 20 weeks we’ll give you the program as well.

We’ll be publishing the 40-week findings later this year. It won’t be a randomized trial at that point, but it’ll still be interesting.

I should mention Sanjay Gupta, the chief medical correspondent of CNN who is a neurosurgeon himself and the associate chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at Grady Memorial Hospital in Emory. He filmed the first cohort of patients 5 years ago and filmed them again a few months ago, focusing on one patient in particular. She was able to follow the program for 5 years and showed even more improvement than she did after 20 weeks. Her mother, her grandmother, and her sister all died of AD.

We have four patients who are homozygous APOE ε4 carriers, and one of them did not follow the program (he was one of the few patients who didn’t). Of the other three, one stayed the same and the other two improved, even though they’re homozygous and ineligible for lecanemab and drugs like that. Now, that doesn’t prove anything, but it’s another area for investigation.

To be able to give hope to people who have been told that they can only get worse, or at best slow down, is a wonderful thing. Not everybody gets better. The more you change your lifestyle, the more likely you are to get better. But there are no guarantees. I hope this will motivate other scientists to do large-scale studies over longer periods of time with more diverse groups of people.

LaFaver: Thank you for sharing your findings and digging a little bit deeper into the details. It’s really encouraging data. Where can people go to find out more?

Ornish : The full PDFs of all these studies are on our nonprofit website, www.pmri.org — that stands for Preventive Medicine Research Institute. For more information about the clinical programs, go to www.ornish.com. As I said, the program is covered by Medicare for heart disease, and we’re in the process of trying to get it covered for AD too. I appreciate the chance to share this information with your audience. Awareness is the first step in healing.

LaFaver: Wonderful. I encourage everyone to read the paper to learn more, including the details of the interventions. Thank you again for talking with us today.