Becky Kennedy, a child psychologist known as Dr. Becky to her 2.4 million Instagram followers — making her one of the most influential figures in contemporary parenting — believes that parents should approach their roles with the same degree of seriousness as medical students training to be doctors. “To me, being a parent is that level of importance of a job,” she told me recently.

Kennedy first rose to prominence on social media during the darkest lockdown days of the pandemic by making simple front-facing Instagram videos in which she role-played common scenarios — a child who is anxious, a child who lashes out angrily at a sibling — and offered suggestions for specific things for parents to say and do. The promise of a parenting script turned out to be a relief for floundering, isolated parents. Since then, her company, Good Inside, has become a parenting-advice juggernaut that encompasses a best-selling book, a podcast, and a subscription-based online community and content library ($276 a year) on top of a steady stream of videos on Instagram and TikTok.

In October, I went to see Kennedy, who lives on the Upper West Side, across town at the 92nd Street Y, where she was appearing in conversation with Chelsea Clinton. Before the event, impeccably turned-out uptown moms lined the sidewalk in anticipation. A security guard hollered down the block, announcing the formation of a line for Chelsea Clinton.

“We’re here for Dr. Becky,” a woman with a Chanel purse corrected him.

While the Good Inside community is global — there are currently more than 48,000 paying subscribers located in more than 100 nations — the home crowd is of a certain class. Many had come to the talk at the Y in groups of friends, and the din of animated conversations filled the venue lobby, with lots of enthusiastic waving to acquaintances across the room. There were very few men in attendance. The audience felt like an impromptu gathering of an elite corps of highly effective school fundraisers. One group of four attendees I met all have children at the same elite private school where Kennedy sends her children. “She’s just a great person,” one offered. “Just like how she is in her videos.”

On social media, Kennedy, who is 41, wears little makeup and appears to create content spontaneously, whenever and wherever an idea occurs to her — during what she calls “margin times,” when she’s on her way to or from the subway or walking to pick up her daughter at ninja class. “Calling it a process would be generous,” she says of how she comes up with videos. “I’m always having a new idea, and part of that is because I have real children who give me inspiration. I do just put my camera in front of my face and start talking.”

Sometimes she sounds breathless, as though she has an urgent message that can’t wait another minute. Her delivery is intimate but firm, like an unsolicited pep talk from your most intense friend. But onstage at the Y, polished in heels, a dress, and a gold Cartier LOVE bracelet, she was a gifted speaker in full control, ready with asides and anecdotes.

During their talk, Clinton asked about Good Inside’s origins, and Kennedy shared a story that has become part of the brand’s lore: In her private practice as a family psychologist, she became increasingly uncomfortable with her training, which was to advise clients to give their children punishments, sticker charts, and time-outs. “At the time, it made sense to my logical brain,” explained Kennedy. “Kids need consequences for their actions because adults have consequences for their actions.”

But she began having a “nagging suspicion” when sitting with families and their misbehaving children that, in truth, she liked the misbehaving kids. She found herself thinking that these children were acting out because they were struggling with feeling misunderstood. The nagging suspicion became stronger until one day, in a session with a family, she interrupted herself in the middle of instructing them on how to give a time-out. “I’m sorry,” she recalls saying. “I really don’t believe anything I’m telling you right now.”

Kennedy says her conviction that something was wrong with modern parenting came before she could articulate much more of what would become the Good Inside philosophy. She often repeats that children are born with the entire range of human emotion and none of the skills required to cope with it. In the world of GI, a parent’s job is to teach those skills not through instruction but by modeling them. Parents are invited to experience parenting as a personal transformation. In the argot of our times, it’s parenting as emotional upskilling.

Later in their conversation, Clinton asked Kennedy to elaborate on one particular upskill, a method she calls PNP — “play, no phone” — which is Kennedy’s approach to parents’ fraught management of their own — not their children’s — screen time. “Every parent navigates the connectivity that technology facilitates while not wanting our children to grow up co-dependent with a piece of hardware,” Clinton ventured tentatively.

“First of all,” Kennedy said to the audience, “this is not a shame moment.”

“Our kids are always paying attention to the way we give attention to them. How present we are, how available,” said Kennedy. But a device-free home, she added, is not realistic. Instead, she suggests parents spend dedicated periods of time — however long or short they deem appropriate — playing with their children with their phones hidden away (“For me, it has to be behind two doors”). “Our devices steal our sense of enoughness,” said Kennedy to murmurs of agreement. To endure the separation from our phones, she recommends we get “really hyperbolic” and say to ourselves, “There’s nothing in the world more important than what I’m doing right now. And I’m doing enough.”

That nagging, unanswerable question of what constitutes enough is what has given rise to the Dr. Becky phenomenon. Among many of today’s parents, there is a twin desire: for reassurance that they’re doing their best and for guidance on how to do better.

It’s a long way from D. W. Winnicott, the British child psychoanalyst who popularized the concept of the “good-enough mother” in the mid-20th century. He argued that most parents, left to their own devices, should be able to trust their instincts and that letting your child experience frustration was part of preparing them for life. Most of us basically know what’s best for our children, Winnicott argued.

Winnicott’s easygoing approach does not fit easily with the spirit of our times. “People accept that athletes have coaches, but they don’t think parents need coaches. But they do,” Kennedy’s business partner Erica Belsky told me in the fall. “One of our goals is to elevate the role of the parent, to make it into something you might hire a coach for.”

After the talk, Kennedy went backstage for a meet and greet with members of the GI online community. The energy was evangelical. One mother of two told me that GI had transformed her relationship with her kids and even with her husband. Another told me that she had stopped socializing with the friends she’d known before she’d discovered the community — they just weren’t on the level.

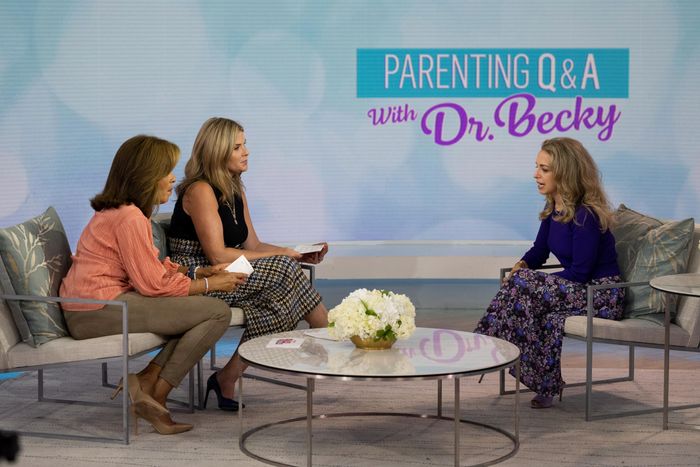

September 2022: On the Today show, soon after publishing Good Inside, where she explained how to approach children’s misbehavior with “the most generous interpretation.”

Photo: Helen Healey/NBC via Getty Images

One of Good Inside’s most controversial tenets is that consequences and punishments are not effective ways of teaching kids how to behave. Instead, Kennedy advises parents to set boundaries and enforce them while maintaining a “connection” with their children to teach skill-building. This might mean picking up a screaming child and carrying them out of the park while repeating quietly, “I know it’s hard to leave the park, but I told you it was almost time to go, and now we are leaving.”

The parent as “sturdy leader” is a recurring character in the world of Good Inside. Rather than letting children and their unruly emotions run the show, the sturdy parent projects calm authority. In the midst of turbulence, she often repeats, passengers don’t want to be given control of the plane, do they? No: They want to know the pilot has everything under control. Parents should embody the same assured confidence an airline pilot does.

The sturdy leader personifies “co-regulation,” a popular concept in many parenting circles today, GI included. The prevailing belief is that children can’t learn to control their emotions if their parents can’t do it too. (That’s why yelling at a kid to calm down has never worked.) Good Inside teaches that learning to regulate behavior is just a matter of “making skills a match for feelings,” Kennedy says. Where older parenting objectives like self-discipline bring to mind suppression, “skill-building” evokes expansion. Kennedy’s parenting advice spreads the responsibility to self-regulate equally between parents and children with plenty of effort to go around.

While the emphasis on emotional intervention, boundary-setting, and co-regulation did not originate with Good Inside, Kennedy’s distinctively snackable content has pushed these concepts into the parenting Zeitgeist. In one recent video, she begins in the role of a parent, asking a question she gets a lot: “Dr. Becky, if I don’t punish my kid, how is he ever going to learn right from wrong?” Okay, Kennedy counters, let’s break this down. “You know how kids learn right from wrong? From talking to them. And from watching your parental behavior. What do I mean? My kid hits his sister. I don’t have to punish him to show him right from wrong. I can talk to him: ‘Hey, what’s going on? I know you know not to hit your sister. So something must have been happening. Something must have felt out of control. Let’s get to the bottom of that and then we can figure out something else you can do that keeps everyone safe. You included.’” The role-play over, she addresses the camera: “Hopefully, we’re modeling how to regulate our emotions. The idea that we have to punish a kid to teach them right from wrong has been passed on to us through generations. And I urge you to be a cycle-breaking parent who says, ‘Wait, that doesn’t make sense!’”

The comments that spool out below Kennedy’s content are exceptionally ingenuous. People ask for clarifications and jump in to offer thoughtful advice. A rhetorical style has emerged, as the audience has adopted Kennedy’s language as its own, repeating her catchphrases: “Two things can be true.” “What’s the most-generous interpretation?” Reply threads expand, revealing an audience eager to dig into the finer points of topics like the pros and cons of withholding the iPad. The world of Good Inside can feel like a padded room of parental conscientiousness, where no detail is unworthy of parsing. It can also make an impatient parent start to nervously self-assess.

Kennedy has reassurance for those folks, too. Yelling at your kids, she reminds us, is inevitable. We’re only human, after all. This past fall, Kennedy did a round of media appearances based on the ostensibly shocking premise that Dr. Becky says yelling at your kids is bound to happen. It was in support of her TED Talk on the topic of repair, which is how she frames the process of apologizing and explaining yourself after having lost your temper, through which parents can help their children learn about emotional triggers by modeling self-awareness about their own.

Kennedy’s emphasis on calm, validating speech rather than threats and consequences frequently gets GI linked together with “gentle parenting” — an association that GI adherents are quick to refute.

“Gentle parenting has the same empathy and validation as Good Inside but without the boundaries that are a huge part of the GI approach,” emphasized Grace, a mother of two from Columbus, Ohio, who serves as a parent mentor in the online community. The two philosophies do share a belief that how parents talk to their children has major consequences for their future well-being. Call it a philosophy of deterministic parenting. “It’s really about these little micromoments,” said Grace. “What am I wiring my kids for? Am I wiring them for shame and punishment? Or am I wiring them for resilience and confidence?”

April 2023: During her TED Talk, discussing the importance of “repair” after parents yell at their children.

Photo: Jasmina Tomic/TED

Kennedy often appears less like a clinician than like a translator of children’s emotions. She is petite — she did gymnastics in high school — and there are instances in her social-media role-plays when she rather spookily disappears into the role of a child. She sometimes seems on the verge of tears while reflecting on what it’s like to be one.

Becky Prince grew up in Scarsdale, one of three children to a mother who was a social worker and a father who was a commodities trader. “I experienced a lot of pain as a kid,” she told me, even though “nothing objectively scary was happening in my life.” From a very young age, she was struck with terror in bed at night, afraid to call out to her parents lest an imagined intruder locate her first. “I just think we underestimate how many big thoughts and feelings and fears little kids have,” she told me. “I remember being taken very seriously by my parents and never being made to feel like I was dramatic or crazy.”

Kennedy first went to therapy at around 7 or 8 because she was so afraid of separation or being kidnapped that she struggled to sleep. No one else she knew at the time was in therapy, but she doesn’t recall feeling self-conscious about it: “In my family, it really felt like support and not judgment.”

Lisa Zuckerwise, a friend of Kennedy’s since the sixth grade who is a maternal-fetal-medicine physician in Charlottesville, Virginia, recalls that Kennedy’s big emotions weren’t a source of shame. Kennedy didn’t like sleepovers or slumber parties, and her friends adapted to accommodate her. Instead, they often gathered at the Kennedy family home, teaching themselves to play competitive mah-jongg and later having high-school get-togethers there.

Kennedy’s second experience with therapy came in late high school, when she developed anorexia in the wake of a sports injury that derailed her routines. The treatment was effective. She went on to study psychology at Duke as an undergraduate and earn a Ph.D. in clinical psychology at Columbia, where she worked with children doing play therapy. After graduating, she went into private practice, treating adults and adolescents. In her practice, she observed that harmful patterns in adulthood usually began as coping mechanisms in childhood. “I remember thinking, What if I just took all the knowledge I have from all of my years of working with adults in therapy and reverse-engineered that knowledge to help parents to do all this stuff early on with their kids?”

Among Kennedy’s many signature concepts, the “deeply feeling kid,” or DFK, may be her most influential. DFKs, according to the Good Inside worldview, are “more porous to the world.” These are children whose emotions feel huge and overwhelming, and who, according to Kennedy, live in fear of being overtaken by them. They experience acute shame and anxiety that their parents could also find them, and their feelings, to be entirely too much to bear.

Kennedy saw herself in these children: “They are literally the most misunderstood group of kids in the world, and they end up getting parented in a way that exacerbates all their greatest fears.” She would sometimes see parents of what she now recognizes as DFKs in her practice. These parents seemed unable to make the standard parenting advice work. No matter what they did, their kids would yell at them, “Get away from me!” At the time, Kennedy couldn’t figure out why progress was so elusive.

She had an epiphany after the birth of her second child. She describes her first child as having been fairly “linear” in his reactions to her. If she comforted him during a sad moment, he would react by feeling better. But where her eldest son would begin to calm down during such interventions, her second child, her daughter, would escalate.

Kennedy has come to believe that deeply feeling kids experience unbearable shame when they are called out for rudeness or misbehavior. But rather than reacting to a reprimand by quieting down or sulking, their anger will escalate. To parents, these situations can feel impossible to manage.

“Most kids, when they’re upset, you can walk into the front door of their house,” she said. “But a deeply feeling kid will slam the door in your face. And then you’re like, Fine, I’ll stay outside. And the kid will feel like, See? I really am as bad and toxic as I feared. Nobody will be in this with me. And you’re like, But they told me to get out! So DFKs can’t take ‘front-door strategies,’ and they also can’t be ‘alone in their house’ — no one can. So I kept being like, These kids need side-door strategies. I started developing these sneaky side-door ways with my daughter, along with some of my clients.”

Kennedy sees side-door strategies as a way of maintaining an emotional link with your child through their meltdown, gradually helping them to calm down. On an episode of the Good Inside podcast, a dad called in asking how to deal with his 6-year-old son, Aiden, a DFK who couldn’t handle saying good-bye to his friends. Every playdate would end in a tantrum. “My thought is that it’s really hard for Aiden to feel disappointed with friends — it feels too big to regulate, and it comes out in lots of different intense ways,” said Kennedy. She suggested to the father that when Aiden gets upset, he should model good behavior on his behalf. “Go to his friend and say, ‘It can be really hard for Aiden to say good-bye, so I’ll say good-bye for him. Bye! That was super-fun! Hope to see you at my house again soon!’” By removing the stress of shame, Kennedy counseled, the dad was creating conditions in which Aiden might learn to behave differently next time.

The Good Inside insistence on depathologizing kids with “big feelings” has been a form of absolution for untold numbers of anxious parents. “There is so much about parenting — the shame of it — that no one talks about,” said Abhi, a GI community member from upstate New York. Elena, a community member from Oregon, told me that Kennedy’s advice has helped her better understand herself while learning how to handle her daughter’s “huge emotions.”

Good Inside’s methods of teaching your child to self-regulate require a degree of compassion that many parents did not as children receive from their parents. Reparenting, or parenting your children as you wish you had been parented, is a frequent topic on GI message boards. The roots of the idea go back to the 1960s and ’70s; it was often lumped together with New Age therapies, until its recent entry into the mainstream, partly thanks to Good Inside. For millennials whose parents were checked out because of divorce or career stress, the act of reparenting promises to be a retroactive fulfillment of the wish for more attentive caregivers. It also suggests that parenting can itself be a form of autotherapy.

Kennedy and I spoke several times beginning in July. Early on, I asked her what she would say to parents who might feel uncomfortable prioritizing their children’s feeling of inner goodness during those moments when, say, the children are behaving like little brats.

“One of the reasons it might feel weird to you is if you’re parenting your kid in a way that’s in opposition to how your parents would have handled those moments. Your body is literally going to feel haywire,” Kennedy said. “Our body likes what’s familiar more than what’s good for us. So — yes. It will feel uncomfortable to believe your kids’ feelings, if you weren’t used to that.”

October 2023: Onstage at the 92NY with Chelsea Clinton.

Photo: Michael Priest Photography

The emphasis on reparenting yourself while parenting your child can make it seem like everything in life can be reduced to, or correlated with, how you parent: It’s parenting all the way down. The omnipresence of Good Inside’s content delivery reinforces this feeling. You can sign up to receive occasional text messages from Kennedy that offer support in areas you indicate you struggle with. When you press PLAY on a workshop video like Mom Rage: How to Stay Calm Amidst the Chaos, an email will appear in your inbox from Kennedy that says, “You’re amazing. The hardest part of anything is starting it, and today you did just that. Pause and recognize the huge step you’ve taken to support your child and yourself. And that is truly enough for today.”

Kennedy’s first viral Instagram post, from the early days of the pandemic, counseled parents to be mindful that their children were watching them for cues about how to manage their anxiety about COVID. By late 2020, as her Instagram following grew, she’d reached out to Belsky, a friend she had met in her clinical-psychology Ph.D. program at Columbia. Belsky, who had done addiction counseling in New York after graduating from Columbia, is married to Scott Belsky, an entrepreneur and tech investor.

“She knew she had something,” Belsky told me. “So we met and started planning what we could do with it.” Belsky and Kennedy named their company Good Inside after one of Kennedy’s core principles: that all children are good inside and that parents should teach children to believe that about themselves.

Belsky and Kennedy live in twin uptown bubbles: Belsky on the East Side, and Kennedy, with her husband, Colin Kennedy, who works in fintech, and their three children, on the West. “Two different worlds,” joked Belsky. They “bootstrapped” the company through its first two years, reinvesting the money they earned. According to PitchBook, Good Inside recently raised $10.5 million in its first round of venture-capital fundraising from Inspired Capital, an early-stage VC founded by millennial personal-finance guru Alexa von Tobel, G9 Ventures, and other undisclosed investors.

According to Belsky, they’re focused on growing the subscriber base of the Good Inside community. The price of admission gets users access to an expanding library of resources, which Belsky and Kennedy pitch as the solution to the problem of blindly Googling in search of parenting advice. The virtual community engages the help of trained GI clinicians and parent mentors to help answer questions and act as moderators. One parent mentor I met at the 92Y event, Carolyn Ismach, a stay-at-home mom of two from Bergen County, New Jersey, devotes significant time to the effort. The mentor work is unpaid, but mentors do receive perks such as free membership. (“I know I tell you this every time I see you,” she said to Kennedy at the meet and greet as the two of them clasped in a hug, “but you changed my life.”)

Good Inside’s ambition is to offer an answer to anyone’s question, along with the community support to help parents implement solutions. No longer would a single book be enough to set a parent on the right path. This is parenting advice as a service — with a default setting of “auto-renew.”

Good Inside’s hefty fee relative to most online subscriptions translates into the spirit of its community: people willing to pay to participate in a discourse with a firmly defined set of values and goals. Still, frustration, albeit politely and humbly expressed, is a not uncommon characteristic of GI community spaces. Parents often post about feeling like they can’t make the progress they’ve been promised. “I constantly feel like I’m walking on eggshells and I literally don’t know what to do or say ever anymore because nothing helps,” a recent post in the DFK community space read. But even these are opportunities, within the GI world, for growth. Under every cri de coeur from a parent who’s struggling to apply the Good Inside strategies are comments of bright encouragement and affirmation.

“When someone says something isn’t working, I totally believe them,” Kennedy told me. “I would validate that it’s really hard, and they are really trying. Then I’d want to know what their definition of something working is. I’d want to know something specific that would give them the feeling of, like, a two-degree shift. That’s usually how change works.”

Depending on what a parent is trying to change, Kennedy might recommend personal therapy: “I always say a Good Inside membership isn’t a substitute for personal therapy.”

Kennedy thinks that social conditions — the onslaught of social media and the world-historical events inevitably freaking out parents — are giving rise to an increasing number of DFKs. “These kids are especially oriented by attachment because they’re so terrified of their extra-helplessness in the world,” she explained. “And parents — me included! — are more distracted than ever. So these kids are more overwhelmed and less connected. So, yes, you’re going to see more of these struggles.”

One of the most striking aspects of the Good Inside approach is that it appears to emerge from the assumption that children feel worried and alone. Good Inside suggests that children need emotional interventions from their parents in order to thrive. Interventionist approaches to American parenting have ratcheted up over the decades, as the latchkey parents of the ’80s gave way to the ’90s and aughts helicopters, followed by the snowplow parents. The trend has grown in tandem with the increasing precariousness of everyday life. Our professional success and economic stability is never certain, so we diligently professionalize and game-plan different outcomes. Through hard work, we try to skirt disaster.

Now our focus seems to have progressed into a new phase of intervention, beyond the level of logistics and safety, on the level of emotions. Whereas parents of previous generations may have raised us in the hopes that we’d one day be financially independent, Good Inside parents hope their children won’t carry emotional wounds. They seem to worry about the corrupting influence of shame and anxiety more than instilling a strong work ethic. Kennedy’s exhortation to approach parenting like a medical student in residency gestures toward acute anxiety about children developing resilience in an indifferent world. By taking our roles seriously, we might project some order into their uncertain futures.

But children don’t follow the same trajectories as careers, and famously they like to figure things out for themselves. In a recent article in the Journal of Pediatrics, three researchers argue that the rise in depression among children and teens — rates have been increasing steadily over the past four decades with visits to hospital emergency rooms for reasons of mental health doubling between 2011 and 2020 — may be traced to an overall decrease in independent activity during childhood. Not being left alone enough, the researchers argue, is harming kids.

The author Astra Taylor has argued that insecurity is a state of being that capitalism feeds on and reproduces. This insecurity can form the basis for our parenting, too. Our consumer selves are provoked by a sense of need or lack — of expertise, of reassurance, of confidence — and the advertising and media that we’re continuously inhaling keeps us in that perpetual state of provocation. It’s no wonder Kennedy has to remind parents to be sturdy. It’s also no wonder they’ve latched on to her advice.

If the deeply feeling kid is a product of their environment, then so too is the deeply intervening adult. Perhaps there’s another reason why many parents would rather engage with their children on an emotional rather than a disciplinary level: Children’s emotional worlds, unlike their material futures, are areas where anxious parents might actually exert some control.