Your mileage may vary. This is an advice column that provides a unique framework for thinking through your moral dilemma. To submit your question, fill out this anonymous form or email [email protected]. Here is a question from readers this week.

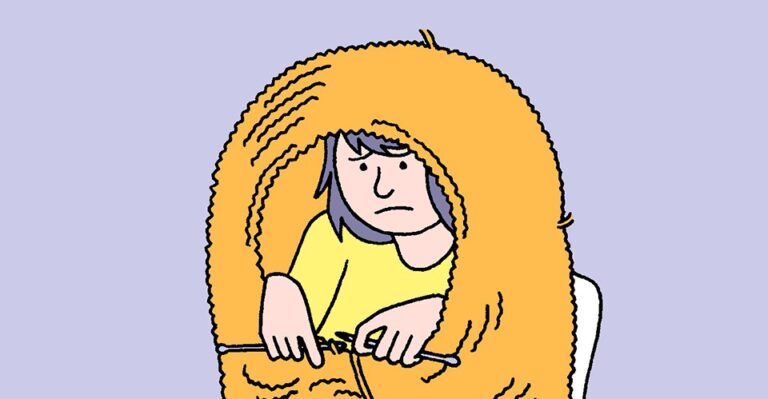

Recently, I have been avoiding news about the current political situation to help my mental health. That really helps. I have not completely buried my head in the sand. I still get some information from things leaking to others and social media (I use it less) and things like John Oliver, but overall, I didn't think about it much.

But obviously I feel a bit guilty about it. I see people constantly talking about how everyone needs to help as much as possible, and how indifference and the resulting inaction are exactly what people in power want. I think my dilemma is that question. By choosing to take a break, are you giving them exactly what they want? Part of me knows that if my mental health is bad, I probably can't help very effectively, but another part of me knows that the world won't pause with me.

I think your question is basically about caution. We usually see attention as a cognitive resource, but it is also an ethical resource. In fact, it can be said to be a prerequisite for all ethical behavior.

“Attention is the most unusual and pure form of generosity,” writes Simone Weil, a French philosopher of the 20th century. She argued that simply paying close attention to others can develop the ability to understand what they really are. It allows us to feel compassion, and compassion drives us to action.

It's extremely difficult to truly pay attention to, Weil says. Because suffering people need to be seen as “not as a specimen of the social category labelled “unhappiness,” but as men, just like us, who have been marked specially by suffering.” In other words, you cannot “have the joy of feeling the distance between him and yourself.” You must recognize that you are a vulnerable creature.

So when you “pay attention”, you are really paying something. You pay with your own immortality. It costs you quite a bit to get involved in this way. That is the “pureest form of generosity.”

Doing this is hard enough, even in the best circumstances. But today we live in an age where the ability to pay attention is under attack.

Modern technology has given us a wealth of information that is constantly streaming from around the world. there is excessively To pay attention, we live in an exhausted, information overload. That's true even when politicians intentionally “overflow the zone” with the constant flow of new initiatives.

Furthermore, as I have written previously, digital technology is designed to break down the focus that reduces the ability to moral attention. This is the ability to notice morally prominent features of a particular situation so that it can respond appropriately. Think about your Facebook feed and find an article on your Facebook feed about children who are seeking help but starve Yemeni children.

Do you have any questions in this advice column?

The problem is that our attention is not only limited and fragmented, but we also don't know how to manage the attention we have. As high-tech ethicist James Williams writes, “The main richness of risk information is not that your attention will be. occupation or I've used up By information…but rather it does Lose control Caution process. ”

Think of the Tetris game, he says. The abundance of rainy blocks on the screen is not a problem. Given enough time, you can figure out how to stack them. The problem is that they speed up. And at extreme speeds, your brain can't process it very well. You start to panic. You lose control.

The same goes for a constant news hose. Exposing it to the rapids makes you confused, confused, and ultimately desperate to escape the flood.

Therefore, more information is not always good. Rather than trying to incorporate as much information as possible, we should try to incorporate it in a way that will help our true goal of increasing the ability to moral attention, or at least preserve it.

That's why some thinkers have recently spoken about the importance of regaining “sovereignty of attention.” You must be able to deliberately direct the attention resources. If you strategically withdraw from an overwhelming information environment, it is not necessarily a failure of your civic duty. It could be the exercise of your agency that will ultimately help you become more meaningful in the news.

But you have to be intentional about how you do this. I'm limiting your news intake, but I recommend coming up with a strategy and sticking to it. Instead of the slightly accidental approach that mentions “things leaked to my social media,” consider identifying one or two major news sites to check for 10 minutes each day while drinking your morning coffee. You can also subscribe to newsletters like Vox's The Logoff. This is specifically designed to update you with the most important news of the day, so you can adjust all the extra noise.

It's also important to consider not only how you can draw attention from the news, but what you'll invest in instead. You mention hobbies and spending more time on people around you. That's great. However, be careful not to cocce yourself exclusively in the personal realm. It's a privilege that many people don't have. You should not be involved in the political realm 24/7, but you are not completely exempted either.

One of the valuable things you can do is take the time to train your moral attention. There are many ways to do it, from reading literature (as recommended by philosopher Martha Nussbaum) to meditation (as recommended by philosopher Martha Nussbaum).

I personally benefited from both of these techniques, but one of my favorite things about meditation is that I can do it in real time while reading the news. In other words, it doesn't have to be just what you do instead of news consumption – it could be a changing exercise how You pay attention to the news.

Even as a journalist, I find it difficult to read the news. Because it's painful to see stories of people suffering. I usually feel what is called “compassion fatigue.” But I've learned that it's actually a misnomer. It really should be called “empathy fatigue.”

Despite the often confusing concepts, compassion and empathy are not the same. Empathy is when you share the feelings of others. If others are feeling pain, you will feel pain too – literally.

That's not the case with compassion. This gives you a sense of warmth towards those who are suffering and motivates them to help them.

Practicing compassion both helps us to make us happy and others happy.

In a study published in 2013 at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany, the researchers put volunteers in brain scanners, showing horrifying videos of people suffering, and asking patients to empathize. fMRI showed activated neural circuits in the centre of the islands of our cerebral cortex.

They compared it to what happened when researchers took another group of volunteers and gave them eight hours of training with compassion, and showed them a graphic video. A totally different set of brain circuits lights up: for love and warmth, the kind that parents feel for their children.

When we feel empathy, we feel like we are suffering, and it is upsetting. Empathy can help us to notice other people's pain, but can ultimately be tuned to reduce our own feelings of pain, which can lead to serious burnout.

Surprisingly, compassion – it cultivates positive emotions, which weakens the empathetic pain that can actually cause burnout, as the neuroscientist Tania singer has shown in her lab. In other words, practicing compassion helps us make us happy and make others happy.

In fact, one fMRI study showed that, in a very experienced practitioner (Tibetan yogi), a compassionate meditation involving people actually wanting to suffer in the brain movement center, involves preparing the practitioner's body to physically move to help those suffering, who are still lying to the brain scanner.

So, how can you practice compassion while reading the news?

A simple Tibetan Buddhist technique called Tonglen Meditation trains you to suffer rather than leave it. When done as a formal sit-in meditation, this is a multi-stage process, but if you are doing it after reading a news story, it can take a few seconds to do the core practice.

First, you let yourself get into the pain of someone you're seeing in the news. When you breathe, imagine you breathe their pain. And as you exhale, imagine you are sending them relief, warmth, compassion.

that's it. It doesn't sound much – and that alone won't help the suffering people you read. But it's a dress rehearsal for the heart. By doing this mental exercise, we train ourselves to maintain someone else's suffering, rather than relying on “the joy of feeling the distance between him and himself,” as Weil said. And we train the ability to moral attention, so we can help others in real life.

I hope you consume news in moderation, and when you consume it, you try to do so while practicing compassion. If you're lucky, feel like a Tibetan yogi on a brain scanner. Get energized to help others in the world.

Bonus: What I'm reading

- Recently, there is a poem that gave me some relief from anxiety caused by my own newspaper. It is this poem by Wendell Berry, about “how to enter into peace of the wild things that do not impose on life with the prerequisites of grief.”

- I enjoyed this film with Psyche for “Why You Can Be Optimistic in a World of Bad News.” It explains Wilhelm Leibniz's view that ours is not a perfect world, but full of suffering, but it may still be the perfect world.

- This week's News Consumption Questions have led us to revisit the work of 20th century French philosophers Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard. Philosophical bites Podcast. They claim that the media is giving us a real simulation and cut us more from the world because they forget that we are actually getting imitation rather than real. Listen!