I think I've been in a rather bad mood for the past two months, as many readers have doubts. My go-to joke explaining why I think I should land with readers of this newsletter, “I didn't understand how much my overall optimism about the state of the world depends on the fact that Lindsay Graham prefers foreign aid.”

To unleash that a bit, the US spent years spending hundreds of billions of billions of dollars a year on foreign aid, including billions of dollars in vaccinations, preventative devices and treatment for cheap killers such as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis.

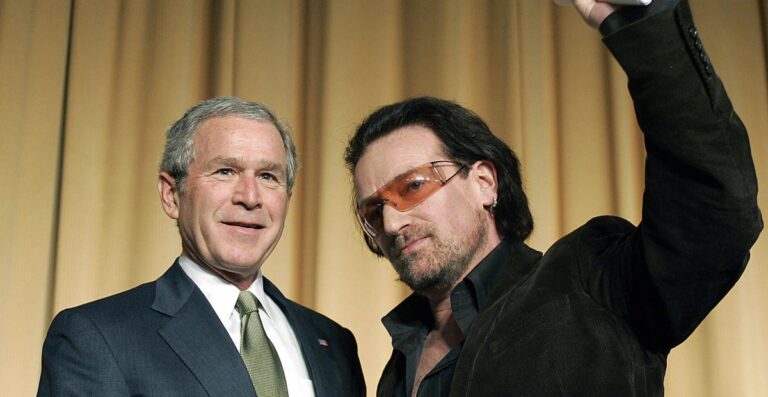

That's it, it did. That's not because liberals in the heart have been in power for decades, but because important groups of conservative Republicans like Graham (and former president George W. Bush and former House Foreign Affairs Chairman Michael McCall) often support foreign aid from honest moral convictions. In fact, aid grew dramatically under Bush, and remained almost constant during President Barack Obama's inauguration time and Donald Trump's first term.

Sign up here to explore the big complex problems the world is facing and the most efficient ways to solve them. It was sent twice a week.

This was clearly not the story of foreign aid in Trump's second term. Already, his Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, is interim president of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), cancelling a program that reaches at least a third of USAID's annual spending. Some areas were hit harder. Efforts to improve maternal and child health have been reduced by 83%, while pandemic prevention has been reduced by 90%. (A federal judge on Wednesday said the Trump administration's efforts to shut down USAID are likely unconstitutional, and ordered the government to restore the USAID system, but everyone is guessing how meaningful the ruling would make.)

Despite Elon Musk's lie that cutting funds hasn't killed anyone, the lack of funding at HIV clinics caused by Musk, Rubio and Trump has already led to children dying. Journalist Nick Christophe has several names of the dead. Working with the Center for Global Development, he estimates that more than 1.6 million people could die within a year without HIV aid and prevention from the United States.

Graham has retreated, especially in the defense of Pepfer, a hugely successful US anti-HIV program. So does McCaul. That wasn't important. The administration seized control of spending from Congress, and the bipartisan coalition that lived up to decades of aid programs was largely powerless, as it was particularly concerned with the issue of foreign aid. Graham's preference for foreign aid has proven to be a positive that is less important to the world than I thought.

This is an example of a broader and surprising trend in American politics that has been unfolding slowly over the past decade or fifteen years. Back at least back to the 1980s, there was a kind of informal cross-party consensus in the United States over a set of policies that opened the world to the US economy, and sometimes governmental resources.

It is an era of elite cosmopolitanism, and that era feels like it's coming or coming.

The Golden Age of Globalists

Of course, during the period I was talking, there were significant and important differences between the parties on a large variety of issues (though between 1986 and 2016, I was not married in either particular year). However, there was a wide range of consensus on many international economic issues.

The parties defended free trade. Instead of negotiating a tariff reduction agreement with Canada and turning the course back, Bill Clinton followed suit with the creation of NAFTA and the World Trade Organization. Bush and Obama followed up on their own trade deals.

Both parties defended immigrants. In 1986, Reagan signed a law offering pardons to undocumented immigrants, and Bush and Obama supported the bipartisan Congressional efforts to grant legal status to those who came after that year.

The foreign aid portion of the consensus is more recent. In the 1990s, USAID hollowed in both staff and fundraising, due to the end of the Cold War (to remove geopolitical reasons to operate in countries where there is risk of communist takeovers), and the persistent assault from Senate Foreign Relations Chairman Jesse Helms (R-NC), an assault on the hostile enemy who is a dedicated opponent of diplomatic aid.

However, foreign aid got a surprising second act under George W. Bush. Not only did George W. Bush pour billions of dollars into Pepfer, he also launched the President's Malaria Initiative (which became one of the world's leading anti-malaria funders) and became the first country to donate to the Global Fund to fight malaria, a multi-layered fan of AIDS, Tobercyrus and malaria. Obama and Joe Biden supported these efforts, and they survived the proposal to cut budgets in the first Trump terminology, supported by bipartisan Congress.

Despite the slightly different timeline, I think it makes sense to put together these three bipartisan consensuses (trade, immigration, aid).

All of them involve American openness to foreign countries. They all benefit from the Bootruger and Baptist coalition, which combines moralists with basic economic benefits.

While some activists supported migration on moral grounds, the US Chamber of Commerce was undoubtedly the biggest booster. Reducing trade barriers clearly supported businesses importing tariff-rich goods and exporting them to customs countries, but many architects of trade liberalization felt a moral duty to use trade to help poor countries such as Mexico and China grow. Foreign aid serves national security purposes to boost America's soft power, but the main motivation for reviving it in Bush, and the main motivation for most of the pro-aid activists I know was a sense of moral obligation.

All three issues reflected a kind of duty of light on the part of the political elite of the United States. They were willing to take important actions to support people born abroad.

Their motivation was not purely due to altruism. The workplace also had economic and geopolitical motivations. But nonetheless, the positive impact on billions of foreign-born people was true.

Why the consensus fell apart

If this elite cosmopolitanism could support large-scale immigration, low-trade barriers and generous foreign aid for decades, why couldn't the Trump administration stop destroying all three?

It's not because the public suddenly changed their minds. Biden's term was a historic period of anti-immigrant rebellion, but when anti-immigrant sentiment was perhaps surprisingly low debilitating, the consensus began to fray in Obama's second and Trump's first term. In June 2016, there were only 38% of voters who said they should reduce immigration, compared to 65% in 1993 and 55% in 2024.

However, in 2016, although the restrictive teachers were in the minority, they became much larger and more influential. The flow of popular refugees from the Syrian civil war meant that the topic had a higher salience in the United States, particularly in Europe. Most importantly, Trump basically broke all social taboos about discussing topics in his main run, and as a result, he not only won nominations as a result, but also won the outcome.

It wasn't a majority position – Trump would eventually lose the popular vote – but it was clearly stronger than previously thought.

The 2016 race also scrambled the politics of trade. Bernie Sanders' stronger than expected challenge to Hillary Clinton has led her to oppose Obama's trans-Pacific partnership, an anti-Chinese trade agreement she eagerly advocated as Secretary of State. She clearly saw it in the strength of Sanders and Trump.

Clinton's ultimate losses by Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania led to a folklore understanding among professional Democrats. do not have Passing protectionist measures to support the condition of a rusty belt is an election suicide.

This made no point. The shock of competition from China and elsewhere hurt these places, but for a long time it was unable to retreat manufacturing employment in Detroit in 1970, so this conclusion means that both parties simultaneously fled public trade, resulting in the US withdrawing from free trade over the last forecast.

As political scientist Margaret Peters argues, it is possible that they argue that immigration support is indeed suffering as trade was liberalised in the 1990s and 00s. Historically, Nazivist forces have been stolen by business lobbies supporting immigration, but the ability of offshore manufacturing to foreign countries has provided an alternative way to bring foreign workers to the United States.

Peters argues that this effect, not just trade transactions, but also standardized shipping containers, undermines immigrant support over time by taking business lobbyists off the board. The bootlegger goes.

However, the saddest case is foreign aid. Why did this small part of the federal budget come for such as the assault this year?

I really don't have a deep structure answer. Foreign aid was once very popular, and voters routinely overestimate how much the US spends on it. It wasn't always popular, it was elite and was in a vulnerable position if someone like Elon Musk chased it. The decline in American conservative religion undermined the power of evangelicals who were very strong supporters of Pepfer under the Bush.

The best explanation for why Musk had such a revenge against foreign aid is that he fell under the influence of the violently opposed conspiracy theorist Mike Benz. He would not have been the first suspicious source to decide against all the reasons Musk absolutely trusts.

But put it all together. And for those who think America can play an important role in creating lives not only here but also around the world, the photos look bleak. In three different domains, a vulnerable coalition was backed whose vision was broken and beat. I haven't thrown it in the towel yet. But the game is going very badly.