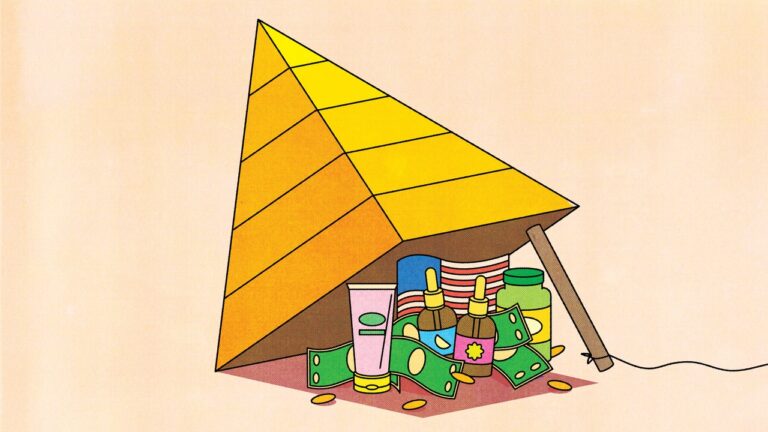

Recently, when the billionaire hedge-fund manager Bill Ackman made headlines for militating against the thought crimes of Harvard undergraduates, the coverage disinterred memories of what had previously been Ackman’s most famous moral crusade: his five-year campaign, during the twenty-tens, to short-sell Herbalife, the dietary-supplement company. Herbalife can be politely called a “multilevel-marketing” or “direct-sales” or “network-marketing” firm, but Ackman and many others called it a pyramid scheme. They believed that, in the words of my colleague Sheelah Kolhatkar, “the company’s real business was recruiting people to recruit more people to recruit more people to sell its products.” These recruits, who are attracted by promises of earning easy paychecks in their spare time, will only make money if they amass a “downline” of sellers beneath them. To maintain their standing in the company, they have to keep buying sketchy, price-inflated inventory, which keeps cash flowing toward the top of the pyramid—the “upline”—even if those pills and potions never leave the would-be seller’s garage, and they often don’t.

A few years into Ackman’s short-sell offensive, the Federal Trade Commission sued Herbalife, asserting that it “deceived consumers into believing they could earn substantial money selling diet, nutritional supplement, and personal care products.” The F.T.C. found that, even among Herbalife members who attained “Sales Leader” status, half were making less than five dollars a month, and half of those sellers were actually losing money. Herbalife eventually settled the suit for about two hundred million dollars and agreed to restructure its operations; in return, the F.T.C. stopped short of calling the company a pyramid scheme, and Herbalife stayed in business. Herbalife’s “nutrition clubs,” where the company lures new members with mysteriously expensive protein shakes and “loaded teas,” continue to haunt storefronts across America. In 2018, Ackman finally abandoned what was reportedly a billion-dollar bet against Herbalife.

M.L.M.s as we know them originated in the early nineteen-fifties, when the eventual founders of Amway were building up a pyramid of food-supplement salesmen and a sales rep named Brownie Wise was organizing the first Tupperware parties. Despite the decades of bad press and costly litigation that ensued, pyramid schemes—or, to be precise, the ostensibly law-abiding companies that happen to be dead ringers for pyramid schemes—appear to be an immovable pillar of the American economy. Part of the problem is one of political will: the elected representatives who appoint and confirm F.T.C. commissioners are often recipients of M.L.M. largesse. And, in any case, the agency is not necessarily the final arbiter of what shape a pyramid can take. In September, a federal judge in Texas, Barbara M. G. Lynn, rejected an F.T.C. lawsuit against Neora, a multilevel marketer of dietary supplements and skin-care products, despite evidence that Neora had misled consumers about the “lifestyle-changing income” they could earn by hawking its products. Lynn was unimpressed by an F.T.C. witness who estimated that ninety-six per cent of Neora’s “Brand Partners” lose money by participating; maybe, Lynn wrote in her decision, these folks just wanted to buy stuff. “Put differently, we may ‘walk away poorer than we started’ after a trip to the grocery store,” Lynn went on, “but because we obtained valuable goods or services in return for our money, that exchange is not characterized as a loss.” The judge’s grocery-store analogy might work better if “we” had a basement full of rotting produce that we tried and failed to sell to all our Facebook friends even though they could get nicer, cheaper fruit at the supermarket down the street.

Then, in January, a Manhattan judge delivered another victory for M.L.M.s by dismissing a federal class-action lawsuit against Donald Trump and the Trump Organization for their endorsement of ACN, a telecom M.L.M. that was promoted on “Celebrity Apprentice.” In that case, the four plaintiffs had lost thousands of dollars investing in the company that the former President had vouched for. (This was not Trump’s only foray into direct sales. In 2009, he licensed his name to a vitamin M.L.M., which was rebranded as the Trump Network, and appeared in promotional videos for the scheme: “Let’s get out of this recession right now,” Trump told prospective sellers, “with cutting-edge health and wellness formulas and a system where you can develop your own financial independence.”) Other class-action lawsuits against a swath of direct-sales companies—including Young Living (essential oils), LuLaRoe (apparel), and Arbonne (nutrition and skin care)—have been either dismissed or settled out of court in recent years.

Regarding the Neora and Trump decisions, the consumer advocate Robert FitzPatrick wrote, “These events should close the door, once and for all, on consumer hopes or support for private lawsuits and ‘cases’ brought by the FTC as useful remedies against MLM’s global fraud.” In FitzPatrick’s view, the fatal flaw in the F.T.C.’s approach is in drawing a line between what it calls “a legitimate MLM” and “an illegal pyramid scheme.” The F.T.C. attempts this distinction by way of mostly unenforceable rules that, for example, place limits on how much inventory a seller can stockpile or what kinds of promises a company can make about the earnings potential of its brand.

FitzPatrick’s pessimism is well earned. A Reddit dive on any number of prominent direct-sales companies will turn up recent cautionary tales of maxed-out credit cards, lost life savings, and basements full of expired merchandise. The popular 2021 documentary “LuLaRich” had a fabulous cartoon villain in DeAnne Stidham, the platinum-coiffed, spider-lashed founder of LuLaRoe, who bewitched tens of thousands of women to buy and (try to) sell phantasmagorically hideous leggings. And the podcast “The Dream,” whose first season unpacked how M.L.M.s prey on women in economically disadvantaged communities, has more than twenty million downloads to date.

The host of “The Dream,” Jane Marie, draws on that reporting for her new book “Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting Americans.” The first chapter is partly set at a pitch party for the sex-toy M.L.M. Pure Romance, a company that would seem, at least from a consumer perspective, to have little reason to exist: the adult-toy site Adam & Eve sells the same line of products (rabbit vibrators, things of that nature) at better prices. The party itself, meanwhile, is depicted as such an excruciating festival of counterfeit enthusiasm and clumsy grift that you can imagine everyone in attendance renouncing not just direct sales but parties and sex toys, forever.

“Selling the Dream” and another recent book, Emily Lynn Paulson’s “Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel Marketing,” try to account for why, despite decades of spurring bad press and intense social discomfort, M.L.M.s retain an unkillable appeal, generating an infinite downline of hopeful apprentices. The classic—though certainly not the only—bull’s-eye of M.L.M.s, Marie and Paulson write, is the suburban or small-town stay-at-home mother. Her household may be stretched thin on a single income, but she lacks the résumé or child-care resources to take on a conventional salaried job. She might also be lonely, low on friends and social capital, and in need of an affinity space, a sense of identity and purpose; these deficits help to explain why military wives are overrepresented among M.L.M. sellers. The direct-sales pitch is that this woman can run a cottage industry from home in her spare time, on her own terms, without having to pay for a babysitter or a business degree, and surrounded by a like-minded community of effusive salespeople and instant friends. M.L.M.s have particular cachet within evangelical Christian and Mormon communities—a 2022 study out of the University of Utah called the state “a global hub for the direct selling business model”—because of the promise of having it both ways: you can be a money-printing #bossbabe and a traditional homemaker all at once. In this context, the M.L.M. presents an ingenious marriage of prosperity theology and conservative gender roles.

In reality, the purported attractions of the job become some of its biggest liabilities. As so many of us learned during the pandemic, being able to work anywhere and anytime can easily become working everywhere and all the time, and an at-home setup hardly obviates the need for a second party to soothe the crying baby or chase the toddler away from the electrical outlets while you’re on your fourth conference call of the day. And, while M.L.M.s promise independence, it’s the company that hoards most of the advantages of the arrangement: an individual direct seller receives no salary, benefits, or paid time off; does not set her own prices or sales goals; has no say on suppliers or marketing strategy; and generally does not even choose what products she is selling.

Both Marie and Paulson draw on their personal connection to the subject. Marie has friends and family who have got caught up in direct sales, and Paulson is one of the infinitesimally small percentage of M.L.M.ers who manage to generate a profitable downline. After years of round-the-clock evangelizing for a company that she calls Rejuvinat—which closely resembles the skin-care M.L.M. Rodan + Fields—and perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars of up-front investment, Paulson aggregated so many sellers beneath her that, every month, she was earning five figures in what was effectively passive income. To put that number in perspective: according to Rodan + Fields’ 2019 income-disclosure statement, two-thirds of the company’s sales consultants earned an average of three hundred and six dollars for the year, and only one per cent earned more than twenty-five thousand dollars, not including expenses.

One of the most insidious effects of M.L.M.s, as “Selling the Dream” and especially “Hey, Hun” make clear, is how they monetize and cannibalize relationships with friends and loved ones. Reps are encouraged to post idyllic family photos with promotional hashtags, turning their kids into branded content. New recruits, Paulson explains, are typically instructed to draw up a “dirt list—that’s the people who would buy dirt from you, people who would support you no matter what.” It goes unsaid, or unrecognized, that the converse should hold more sway: that the people on your dirt list should be the last people you should be plying with snake-oil remedies, because you love and care about them. But, Paulson writes, “MLMs encourage reps to see any concerned family member or friend as a negative person”—or what a Scientologist would call a suppressive person, an adverse influence who is best avoided.

Most critics of the direct-sales industry, including Marie and Paulson, label M.L.M.s as cult-like, starting with their intentionally vague or opaque marketing-speak. As Amanda Montell writes in “Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism,” cults deploy acronyms and bespoke jargon in order to dazzle newcomers who want to break the code and to foster insular bonds among members who speak a language all their own. (In M.L.M.-world, Montell explains, this language can take the form of “nebulous hashtags” and “hazily inspirational status updates,” e.g., “Feeling amazing and my journey is just getting started! #sugarshotresults.”) M.L.M.s also align with cults in their financial vampirism, their with-us-or-against-us mind-sets, and their conspiratorial thinking. At least one bona-fide cult leader got his on-the-job training in direct sales: Keith Raniere, of NXIVM—who is currently serving a hundred and twenty years for sex trafficking, racketeering, and wire fraud—worked for Amway in the nineteen-eighties before starting his own pyramid schemes dealing in vitamins and professional development. (Amazingly, Raniere is not Amway’s most depraved alum. Gary Ridgway, known as the Green River serial killer, once told an investigator that, for a stretch in the nineteen-nineties, “I didn’t do very many killings, because I was in Amway.”)

Of course, most M.L.M.s do not reach anything like NXIVM’s gendered exploitation and cult-like rituals—Avon and Tupperware do not, so far as we know, ask their brand consultants for nude photos as proof of their commitment. But the potential for psychological manipulation and financial ruin is always simmering in the direct-sales stew. What often clouds the judgment of M.L.M. reps and cult members alike is the sunk-cost fallacy, which involves not just the loss of the money you’ve poured into the scheme but also the esteem and fellowship of your fellow-travellers, who have been conditioned to believe, as you have, that your failure to thrive in the sect is due to your own moral weakness, your lack of self-belief. If, say, you cannot move sufficient units of Monat Junior Gentle Detangler at thirty-three dollars per six-ounce bottle, if you cannot persuade your customers to buy your ugly leggings—or, better yet, to become salespeople of your ugly leggings—then maybe you just didn’t want it enough, and that’s on you.

Neither “Selling the Dream” nor “Hey, Hun” is an artful book. Marie’s prose reads like a podcast transcript, full of conversational fermatas (“But think about that for a minute,” “You get it,” etc.) and lazy filler (“But, you know, megalomaniacs gonna megalomaniac”). The last line of the book—the final brushstroke, the exclamation point, the coup de grâce—is “I keep watching though, it’s actually kinda fun.” Still, there is little doubt of Marie’s command of her material or her position as an honest broker. She grew up in a small, rural town near Flint, Michigan, where economic prospects are bleak; she empathizes with people who get ensnared in M.L.M.s and is doing a public service in debunking their claims of financial salvation. “Hey, Hun” feels less trustworthy, and not only because Paulson was so richly rewarded for her complicity in the industry that she now abhors. The book’s most conspicuously evil composite figure is a confusing mashup of several celebrities in the M.L.M.C.U., and all the dialogue sounds like A.I.-generated captions for a Wine Mom meme from 2014. These moments of creative license leave the reader wondering what else Paulson has fudged.

Paulson’s odds-defying success is telling because, in many ways, she doesn’t fit the paradigm of the M.L.M. #momboss. At the beginning of her gig with “Rejuvinat,” she is a stay-at-home mother of five kids, the youngest of whom is still in diapers, and her psychological vulnerabilities are encapsulated in the travel mug full of wine that she often carries around. But her husband makes plenty of money, she always has “a babysitter” at hand (who needs neither a name nor a definite article), and her social networks are robust: she refers to “friends whom we can pass off the kids to” (talk about the American Dream!) and, on page 18, she meets a friend for a drink on ten minutes’ notice, the kind of scheduling feat I haven’t pulled off since grad school. In other words, Paulson has the time, wealth, and resources to build her downlines and to present a façade of luxury and success that other sellers might envy and want to emulate. There is little material reason for her to be drawn to this grubby, grasping, embarrassing work in the first place—which helps to explain why she can succeed at it.

Paulson left Rejuvinat during the pandemic, when many of her M.L.M. comrades began trafficking in COVID denialism and conspiracy thinking; she sympathetically quotes an ex-M.L.M.er who “was horrified by the fact that my entire upline had started posting QAnon garbage on Instagram.” “Hey, Hun,” then, unfolds as a confession of a fully deprogrammed apostate. The insider strength of the book is also a weakness: the authorial voice remains that of the huckster, letting you in on delicious secrets that they don’t want you to know about. What the huckster cannot teach, however, is how to acquire a certain bulldozing charisma—a glossy armor of charm and entitlement, trailing a faint spritz of sociopathy, so relentless and inevitable that its possessor can only seem lightly amused by it. Paulson generally doesn’t go into much detail about how she was able to conscript so many women into her cause, but one anecdote says it all. She tells a story about a seller in her downline who was about to come up short on her monthly sales goal, so Paulson calls the woman’s sister at 11:30 P.M. on Halloween, hounding her with empty promises and emotional blackmail. The poor sister finally relents and purchases a product kit, and the clock strikes midnight.

After leaving direct sales, Paulson eventually switched her professional focus to coaching, another enterprise that requires little in the way of licensure or qualifications beyond confident self-presentation and a nose for an easy mark. (It’s no coincidence that Marie chose life coaching as the subject of Season 3 of “The Dream.”) Paulson founded the paid-membership support group Sober Mom Squad, where two hundred and ninety-nine dollars can buy you the SSP Program, an “evidence-based listening program to help reset your nervous system, guided by certified practitioner, Emily Paulson.” A spot on the Sober Mom Squad costs either fifteen or twenty-nine dollars a month; the costlier option includes guided meditation, webinars, and something called E.F.T., which, upon investigation, refers to Emotional Freedom Technique, a stress-relieving intervention that involves finger-tapping. “You can cancel your membership anytime,” the Sober Mom Squad F.A.Q. reads, “but there are no refunds.” ♦