If you scroll through The Bucket List Family’s videos on social media, here is a smattering of what you’ll find: their then 10-year-old daughter saying goodbye to her great-grandmother’s casket, the family diving with sperm whales in Mauritius, the whole clan embarking on a safari in Madagascar, the youngest son screaming in pain while his dad extracts a parasite from his scalp. It’s all the highs and lows of childhood packaged neatly for mass consumption. The Gee family—which consists of parents Garrett and Jessica and their three kids—has over 5 million followers and subscribers across Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook and uploads new content regularly for their expansive, cross-continental fan base.

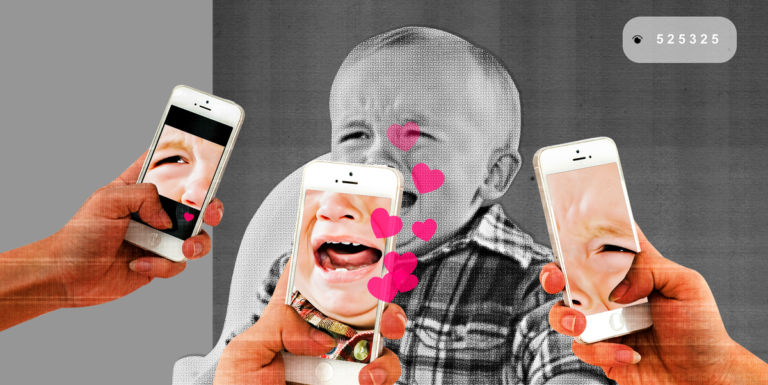

In 2024, the messy business of family vlogging is at an inflection point: to show your kids online or not? Sure, tens of thousands of parent influencers continue to prominently feature their children on social media in a bid to vie for our gnat-like attention spans (not to mention, those lucrative brand deals). But recently, more people have begun to ask unsettling questions about the murky ethics of the entire endeavor. How do you protect the safety and privacy of these kids when nearly every second of their lives is being broadcast to millions? Can toddlers—or hell, infants—meaningfully consent to being part of this chaotic ecosystem before they can even say the word “internet”? What does it mean to stamp their online footprint in ink? Will they eventually share in the profits being made off their work in this almost entirely unregulated industry?

I’ve talked to people on both sides of the issue: those who swear this kind of vlogging is nothing more than exploitation by another name and fans who don’t see a problem with following along on the adventures of their favorite influencer family. High-profile “sharenters” are often reluctant to wade into the debate themselves (although I did get a few to explain why they pulled their kids offline here). You can see the tightrope they’re walking: On the one hand, millions of fans do indeed clamor for content with children and brands are quick to offer sponsorship contracts to willing family vloggers. On the other, there’s an increasingly loud chorus of detractors who find the practice unseemly, even immoral—and, as the New York Times recently reported, certain corners of the internet do contain meaningful risk for so-called child influencers. I’ve been reporting on this topic for two years now because I genuinely want to understand the perspective of the parent creators who freely and regularly share their children. What are their motivations? Do they worry about what their children will make of the decisions that have been made for them? Do these parents have any regrets?

Chances are, if you can think of a vlogging family, I’ve spent the past few months trying to get a hold of them. Finally, after many emails, calls, and DMs, several creators have agreed to go on the record with Cosmopolitan. For this story, I spoke with some parents who are unapologetic about how they choose to show and manage their own children, others who are more ambivalent about their lifestyle, and even the former nanny to an influencing family who offered an insider’s perspective on the uncomfortable dynamics she witnessed.

Garrett Gee, 35, the patriarch of the Bucket List Family, sold his app Scan to Snapchat in 2014 for $54 million. In the aftermath of the sale, Garrett and his family took off for what was meant to be a six-month journey around the world. Gee sensed an opportunity in documenting their adventures and began creating content around the family’s travels. Gee thinks of the family’s social media presence as a means of recording memories. “Our YouTube is our home videos,” he tells me on the phone. “And our Instagram is a photo journal for us. That’s how it started. And when something special or exciting is happening, Dad will whip out his camera because he wants to capture this special memorable moment like any parent would do.” His family clearly doesn’t need the money. Gee insists they do it for themselves.

In snarky subreddits dedicated to critically dissecting the lives of family vloggers (not all that dissimilar from the intensity of a reality TV fandom), Gee is judged harshly for his decision to post content in which his children are crying or seem otherwise vulnerable. How does he respond to that? “Again,” he says, as I wonder if I’m starting to annoy him. “If I’m just creating family videos for our own keepsake and memory, the truth of a family is it’s not just all travels. There’s a lot of times when someone in the family is getting hurt or sad. And so I try to share the full story, the complete story, the ups and downs, everything in our family’s journal.”

Well, okay. The truth of family life does sometimes include tears or saying goodbye to a deceased loved one. But—I push, because I can’t help it—it’s not really a home video, is it? Because home videos aren’t usually for an audience of millions. “Yeah, for sure,” he says. “That’s where it comes down to my judgment, my call as a parent. Because I would never want to put anything out that the kids are either embarrassed by or ashamed of or anything.” Gee notes that he shows his family footage before uploading it and when, on the rare occasion, his kids ask him not to include something, he honors their requests, no questions asked.

I think again about the video where his daughter lightly touches the casket that carries the body of the great-grandmother she was named after or the one labeled “Why is Cali crying?” where the camera closes in on his face as tears stream down his cheeks because he doesn’t want to leave their safari. I wonder what the kids will think of these private moments preserved in the internet’s forever-amber when they’re older.

It’s becoming harder to ignore how producing this kind of content fundamentally alters the relationship between influencer parents and their children. Arianna* saw the unsettling dynamics play out when she spent about a year as a nanny to a prominent influencer family with millions of followers on TikTok. “It was a little nuts because we were always filming and having to look a certain way,” Arianna remembers. On an average day, she would feed the children dinner and then they would begin shooting for TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. She remembers the kids being “exhausted” after the requisite hours of work.

Once, Arianna says, one of the children was playing around, practicing gymnastic tricks, when the mother whipped the camera out. “They started throwing a tantrum because they didn’t want to be filmed,” she says. “And I remember the mom yelling at them, saying, ‘Oh, no, we need to film. This is how we make our money.’ And the kid just got really, really mad, saying, ‘I don’t want to be filmed. I just want to have fun.’”

How did the mother react to the explicit request from her child to not be recorded? Arianna says the mom would remind the children that they liked attention or that their “TikTok family” wanted to see them. Arianna’s employer would also tell the children that the money they were making enabled them to live the way they did. “She was most definitely guilt-tripping them,” Arianna says.

Arianna has a rolodex of stories like this, including the time that one of the kids wasn’t feeling up to a photo shoot but was forced to partake anyway. “She just wanted to sleep,” she says. “She wasn’t really in the mood to do it because of how sick she was.” Sometimes, the children were reprimanded for not being cheerful enough while shooting content; other times, they were chastised for being too giggly, Arianna says.

For these children, there is no boundary between their work and home lives. They don’t clock in at a film set—their own living rooms and backyards are where it all happens. When the camera is ever-present and any moment can be turned into viral monetized content, the pressure to perform is constant. Though she doesn’t work for the family anymore, Arianna still finds herself worrying about the kids and others who may be in similar circumstances. “A kid shouldn’t be your source of income,” she says plainly.

Some parents who are behind today’s popular family accounts are more ambivalent about centering their children, even as they continue to do it. Morgan Fluellen, a 24-year-old mom creator with 1.3 million followers on TikTok, worries there will come a time when her content will embarrass her now-1-year-old daughter Gigi. Morgan first went viral last summer for a 40-second video in which she jokingly tells viewers that before they go and have sex that night, they need to remember it’s too hot outside to be carrying a kid, all the while Gigi is adorably perched on her hip. “I’m about to cry,” she says in the video, which now has over 19 million views. “My coochie is sweating. I don’t know if milk is leaking from these titties or this is boob sweat that I feel on me, but I’m hot.”

Since then, Morgan’s life has changed drastically. She’s racked up followers and endorsement deals, and TikTok is now her job—she posts frequently and most of the content features her daughter. She and Gigi are often recognized in public. “Even just going out to Target and buying a pack of diapers…people are coming up asking to take pictures, even going so far as to ask to hold Gigi,” Morgan tells me. “I just awkwardly kind of back up….There’s no real privacy.”

Though she’s only been on planet Earth for just over a year, the toddler has a dedicated fan base. Commenters, who call themselves Gigi’s “TikTok aunties,” say they wait for her videos every day. Morgan doesn’t see this attachment as strange. “It’s not very weird to me,” she says. “It’s actually very touching. People close to me, her real aunts or my cousins…are like, ‘This is weird.’ But I’ve watched creators in the past where I’m like, ‘Oh my goodness, I love this child.’ I literally feel like I knew them.” Gigi, for her part, is already accustomed to the world of influencing. Morgan says Gigi will grab the ring light and phone and think she’s recording, just like her mom. “I’m like, honey, we need to get you to a playground or something,” Morgan laughs.

Still, Morgan knows what many people think about mommy vloggers—that they’re trading their kids’ privacy for a buck—and sometimes she does second-guess herself. “Part of me is like, Wait, am I exploiting my child?” she says. “Am I posting too much?” As she navigates this new world, she’s made some attempts to draw boundaries. She tries to avoid posting the toddler in only a onesie or a diaper, although older videos she filmed before making that rule are still up on her page. “People can be crazy,” she says. “So I just try to keep her fully clothed and that’s it.”

Many of the family content creators I spoke with seemed aware of the possibility that child predators lurk on their accounts and look at intimate photos of their children (as confirmed by the recent Times investigation), but they’ve found ways to put their minds at ease and tolerate the risk.

All of them seemed to agree: Some of their peers took things too far and shared too much, but none of them ever thought they themselves had crossed the line. Take Veronica Merritt, 38, the mom of 12 behind @thismadmama, who currently has nearly 450,000 followers on TikTok. She mostly posts videos about raising her large family and doing shopping hauls with them at discount stores like Dollar Tree. A few years ago, when she started vlogging, she worried: Was basing her platform on life as a mother of 12 the same as exploiting her kids? But now she sees it somewhat differently—what other job would allow her to be a single mom who stays at home while making enough money to take care of her kids?

But if she could go back? She’d do things differently, sure. “I would have lied more,” she says. “I would have lied about my kids’ names, ages, and location. I would have had them wear masks. But at this point, it feels too late. I’ve already given too much information.” Some of her children prefer to be less involved with the channel, which is fine with Veronica. When they ask, she will crop them out of videos.

Once, she did stop showing her younger kids altogether, but the backlash from her followers was swift. Some viewers even accused her of hiding the kids for nefarious reasons, alleging child abuse or neglect, and she says the kids themselves wanted to get back to filming. “So I was like, fine, whatever. I just started showing them again.”

I can hear Veronica struggling to come to terms with her own choice to broadcast her family online. For most of our conversation, she doesn’t sound terribly concerned about the anonymity her children are giving up. In the next breath, she mentions that people have found their address online and then driven by the family home to yell at her kids. She doesn’t care about her own privacy—she says she’d get online “buck naked” if the price was right—but she does wonder if she should’ve hidden her family’s identities from the beginning. But then again, she interrupts herself, it’s possible the family will parlay their TikTok fame into even bigger opportunities and platforms (a television show has been mentioned, for instance). And if that happens, their faces will be everywhere. She veers back and forth, from worrying about the effect of her decisions on her children’s well-being to believing wholeheartedly in her intent to secure her family’s livelihood. From where she’s standing, there are only so many choices. She’s a single mom of 12 who has stumbled into a way to feed her family that also allows her to stay at home with her kids. And if privacy is the price she pays, she has her wallet ready.

Meanwhile, Adrea Garza, 39, the mom behind @garzacrew (which boasts 4.8 million followers on TikTok), sees her twin daughters’ social media presence as acting. On camera, the 7-year-olds twins, Haven and Koti, film get-ready-with-me videos, skincare routines, and Sephora hauls—but Adrea says they’re each playing a character. “That’s not how they regularly act,” she says. “What you’re seeing is them playing a character.” If she were to go back in time, she says she would create “alter egos” for the girls so the dividing line between their personas and their actual selves were crystal-clear to the audience, some of whom get worked up about 7-year-olds appearing to use retinol. It’s all just a joke, Adrea says. (Just weeks after our conversation, Adrea posted a video in which she introduced “Genny” who, the caption identifies, is “Haven’s alter ego who is skincare OBSESSED.” In another video, Adrea attempts to clarify what she calls the satirical nature of much of their content, though judging by the comments, viewers aren’t convinced.)

Certain influencer families do take it too far, Adrea agrees, such as former-YouTuber-turned-convict Ruby Franke, but they’re the exception, not the rule. “Influencer kids are the happiest kids I’ve ever met. They’re living a dream,” she says. “They’re getting to do what every kid dreams and wishes they can do. If you ask kids in this generation what their dream job is, most of the time they say they want to be a YouTuber or a TikToker.”

Adrea too sets limits on how much time she spends filming her kids (less than an hour total of their week, she says). Other vloggers might show their children in intimate moments—“like when they’re crying or upset or something”—but Adrea won’t do that. She would never show anything related to puberty like bra shopping, she says, and she tries to limit how much she shows one of her daughters in her dance uniforms. “I might post her dancing maybe four times a year,” she says. “Because she is still proud of it and I’m proud of her. But again, we have a large audience and I don’t necessarily want to be putting her out there in a way that’s going to elicit any weird people at all.” But, still, she posts, despite her worries about who the posts may attract. “There’s going to be sick people in the world, and I’m not going to let the small percentage of the freaking sickos out there dictate how I live my life.”

The parenting influencers I spoke with who persist in posting their children are fighting their way through a thicket of contradictions. While it’s true that kids cannot meaningfully consent to being online, they also can’t consent to the hundreds of other decisions parents make for them on a daily basis. At the same time, the gravity of having a childhood spun into content can’t be understated or compared to every other mundane parenting choice. Filming a temper tantrum and then deciding to post it to millions of viewers is just not the same as weighing the benefits of flute lessons versus soccer practice.

These kid influencers are a new kind of celebrity: actors without roles to hide behind and millions watching their every move. They are famous for being themselves. Their likes, dislikes, memories, preferences, hopes, and tears are constantly on display. They are living a warped version of The Truman Show, but they know which camera to look toward. We are past the point when influencer parents could claim to be unaware of the possible effects their choices have on their children. Growing up is painful, joyous, triumphant, and complicated—inviting an audience to have a front-row seat to all of those terrible, precious, aching moments is another thing entirely.

*Name has been changed.

Fortesa Latifi is a journalist with bylines in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, and more. She is working on a book about the experiences of child influencers. You can find her online anywhere @hifortesa.